Expanding the World of Generative Design

Additive manufacturing and generative design have been tied inextricably to lightweighting—but this tech combo can do much more for engineers.

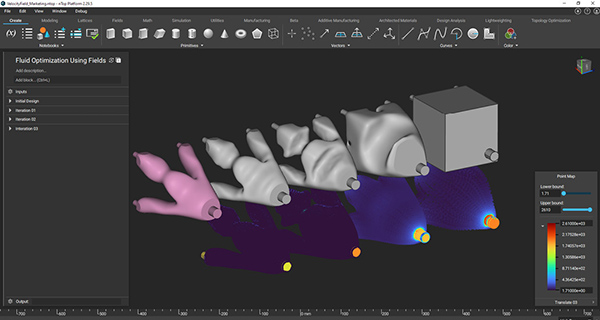

By coupling design and simulation together using Field-Driven Design, nTopology enables the power of implicit geometry to be unlocked in ways that were not previously possible. Image courtesy of nTopology.

Latest News

May 17, 2021

A few years into the debut of generative design software and the mainstreaming of 3D printing technology, it’s now a bit hard to think about one without the other.

The symbiotic nature of the technologies has led to a wave of early use cases focused on creating organically-shaped designs aimed at consolidating or lightweighting parts that couldn’t be produced with traditional manufacturing methods.

Though engineering teams have scored notable wins leveraging the dynamic duo for specific projects, generative design software has capacity to solve for other design challenges in areas such as fluid flow and design for manufacturing (DfM). With the benefits so heavily fixated on lightweighting, engineers could miss out on opportunities to leverage generative design’s full potential to unlock design freedoms and transform workflows in pursuit of highly-optimized products.

“Generative design is way bigger than what’s now mostly understood as it being a design tool for additive manufacturing,” says Thomas Reiher, director of generative design for MSC Apex at MSC Software, a division of Hexagon. “Both produce these organic shapes so it’s a perfect way of working together. But the real promise is bringing the power of computing and the knowledge of multiple systems (such as different physics and manufacturing methods) into an automated way to get to a final design solution.”

Driving Design for Manufacturing

Until now, generative design’s sweet spot has been lightweighting parts such as brackets or casings for output with additive manufacturing (AM). However, the software also can be trained on lightweighting objectives for conventional manufacturing technologies such as computer numeric control milling or casting—a use case often overlooked as engineering teams get caught up in the generative-plus-AM hype.

PTC, which acquired Frustum in 2018 to fold into its Creo portfolio, and zeroed in on that flavor of generative design software primarily because of its capabilities for optimizing manufacturing processes outside of AM, including five-axis milling, as well as a range of physics, says Brian Thompson, CAD division vice president and general manager at PTC.

“We can accommodate manufacturing processes that require a parting line like casting or molding, we can optimize for undercuts for extrusion processes, and ensure the required clearances are there so a design can be machined,” Thompson says. “Not only do we provide the optimal geometry based on structural FEA [finite element analysis] input, we provide that with feedback on manufacturing constraints.”

Jacobs Engineering, a contractor on NASA’s Exploration Portable Life Support System (xPLSS), used Creo Generative Design to come up with optimized and lightweighted designs for brackets, housings and face plates for the space suite, but also to rapidly explore hundreds of combinations of materials and manufacturing processes.

Using Creo 7’s generative design functions, the team was able to explore a full suite of manufacturing methods and apply whichever one was best suited to any given part, says Russell Ralston, xPLSS design manager at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Not only does the generative design function allow NASA and other engineering teams to challenge basic design biases, it can serve as a way of training and evolving engineers.

“It’s about building muscle memory about how to be a better engineer,” says Jesse Blankenship, PTC’s senior vice president of technology.

At Autodesk, the vision is to promote generative design as an exploration tool for multiple manufacturing methods and physics, according to Brian Frank, senior product line manager, generative design and simulation at Autodesk.

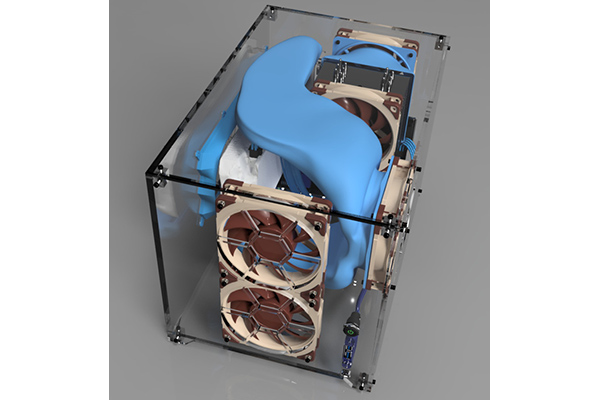

Generative design was applied to fluid flow optimization, helping to create cooling ducting to optimize a tower computer. Image courtesy of Autodesk.

Take material changes as one example: Sometimes the materials used in a design are no longer available or there are recyclability concerns, and generative provides a way to explore how to optimize design changes to accommodate new material choices. Generative design can also come into play to help guide the evolution of a part from concept to volume to determine the best production processes.

“With one design definition in the generative workspace, you can explore how to optimize a design first for AM for prototyping and small production runs, then move to a subtractive or milled process as you enhance capacity, and then to casting for volume production,” Frank says. “Fine-tuning the design to the manufacturing process always gives you the best results.”

In the broadest sense, generative design should serve as a guide to augment engineering expertise, not replace actual engineer decision-making. The system should steer users through the process of identifying whether a lightweight design would work better as casted part or if it would require too much expensive material and work better with a molding process.

“The system should give you different ideas and guide you through the process to achieve your goal,” Reiher says. “It should be able to supervise what the engineer is doing and provide hints on how to improve results and avoid producing parts that are too expensive.”

Generative Design Goes for Flow

Moving forward, MSC Software is exploring how to apply these concepts to new use cases, promoting generative design for fluid flow applications such as optimizing pressure forming molds or cooling channel integration.

The company is also cooperating with an as-for-now unnamed software company to develop the next stage of generative engineering by combining structural generative design with additional engineering disciplines and workflows, Reiher says.

For example, the two companies have collaborated on the redesign of a packaging machine gripper, invoking generative capabilities to create an optimal structure, which in turn was used to drive optimization of a design for internal channel routing.

“Optimal fluid flow was achieved in the most direct and efficient way by coming up with an optimal mechanical geometry and fully automating the process,” he says. “This workflow can be adapted to many other use cases such as pneumatic grippers, oil routing for clamping devices or cooling fluid through fixtures exposed to conventional machining areas of operation.”

Dassault Systèmes also sees potential for flow-driven generative design. Leveraging technology like Abaqus CFD, Tosca Fluid and CATIA, Dassault has built up capabilities on the 3DEXPERIENCE platform to help engineers solve such problems as minimizing pressure drops in ducting or finding feasible flow paths in parts associated with jet propulsion.

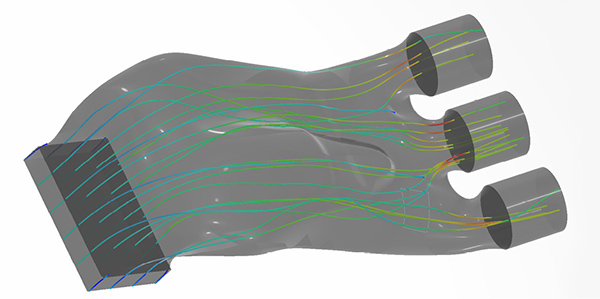

In lieu of traditional workflows that require a back-and-forth workflow and handoffs between siloed tools like CAD and computational fluid dynamics, Dassault’s Flow-Driven Generative Design streamlines the workflow and makes flow optimization capabilities more accessible to mainstream engineers.

“Knowing the inlets and outlets and boundary conditions on each end, you can set up the problem and get an optimal flow path,” says Colin Swearingen, industry process consultant at Dassault. “There are plenty of use cases out there and they’re gaining more in popularity.”

Flow-Driven Generative Design streamlines the user experience and automates generation of flow-driven shapes, removing bottlenecks that make it cost-prohibitive to explore optimized parts. Image courtesy of Dassault Systèmes.

Autodesk recently demonstrated a new fluids solver for its Fusion 360 platform, which enables generative applications to include things like pumps and valves. With proper inlet and outlet definitions that pass through a cooling chamber, Fusion 360 can zero in on the best solution for minimizing pressure drop in a pump design.

From there, engineers can move directly into Fusion 360’s manufacturing workspace to set up the optimal build, resulting in a design that ensures a smooth, continuous flow rate with virtually no turbulence, according to Stephen Hooper, vice president and general manager for Fusion 360 at Autodesk.

Making Generative More Accessible

To ensure generative design capabilities are applicable to other design problems outside of lightweighting and AM production, vendors must lean in to educate the broader audience and make functionality far more accessible to everyday engineers.

For its part, MSC Apex Generative Design focuses on streamlining the process of model setup so designers can make use of the technology. There is also a capability for setting up a “complexity” value that defines how complex a structure should get, which makes it possible to yield more straightforward shapes that lend themselves to traditional manufacturing methods such as casting.

“The designer doesn’t have to set up a specific mathematical value where they need to know what is happening in the background, but can vary the designs based on [a] gut feeling on how they want the design to look or by secondary requirements like cleanability,” Reiher says.

MSC Apex also includes a capability for inputting multi-body simulations from tools such as MSC Adams to simplify the specification of complex loading conditions along with features for producing manufacturing-ready files.

Autodesk is also taking steps to make generative design capabilities more consumable and applicable for other use cases. To make generative output useful and deployable for downstream processes, it’s integrated into the Fusion 360 platform and creates editable geometry to ensure what is produced from generative can be used in CAD or simulation processes without any extra conversion steps.

The Autodesk platform also supports a decision framework, which allows the problem to be defined once and reused for additional exploration as well as for supporting trade-off studies.

“We’ve spent a lot of time to make sure that from an engineering perspective, if you’re leveraging generative design, it’s a productivity enhancer, not a productivity detractor,” Frank says. “If you want mass adoption across the industry, you have to make these things low friction for users.”

Unlike other applications that bake generative capabilities into existing CAD and design packages, nTopology provides a platform that helps engineers create and define their own generative processes for new design creation.

The nTopology platform accomplishes this through capabilities like implicit modeling, which allows you to generate a design regardless of complexity; field-driven design, which ingests real-world physics data to control design parameters; and reusable workflows for building off of previous work.

nTopology’s approach broadens the applicability of the technology and doesn’t pigeonhole generative as the long-time partner for AM.

“The black box approach limits the innovation in the industry—it’s basically saying generative design is just a feature in a CAD tool, not a shift in the way we make parts,” says Bradley Rothenberg, CEO, nTopology. “The key is generative design is a new way to think through how to produce a design object. It’s not replacing the way we design everything, but for certain applications, it can solve the design problem in a better way.”

More Autodesk Coverage

More Dassault Systemes Coverage

More Hexagon Coverage

More Hexagon MSC Software Coverage

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Beth Stackpole is a contributing editor to Digital Engineering. Send e-mail about this article to [email protected].

Follow DE