Blending Reality with Pixels

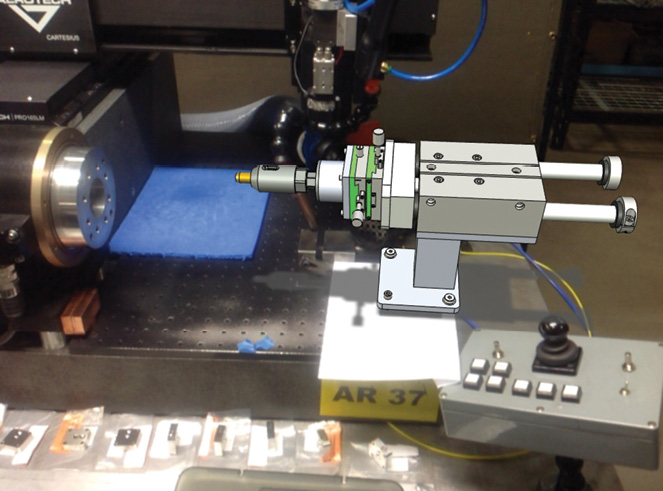

Bob Conley from Interactive CAD Solutions uses iPad-powered augmented reality to check how SOLIDWORKS models would fit into the client’s machinery. Image courtesy of Interactive CAD Solutions.

Latest News

August 3, 2015

Bob Conley from Interactive CAD Solutions uses iPad-powered augmented reality to check how SOLIDWORKS models would fit into the client’s machinery. Image courtesy of Interactive CAD Solutions.

Bob Conley from Interactive CAD Solutions uses iPad-powered augmented reality to check how SOLIDWORKS models would fit into the client’s machinery. Image courtesy of Interactive CAD Solutions.Two years ago, while attending Dassault Systemes’ SolidWorksWorld user conference, Bob Conley saw a demonstration of the eDrawings mobile app, a CAD file viewer for tablet users. What won him over was the app’s augmented reality (AR) function, which enabled users to project CAD models into a live feed from the iPad’s camera view. So he promptly purchased an iPad and the eDrawings Pro app from iTunes. The $810 investment ($800 for the device, $10 for the app) laid the groundwork for AR in his design consulting business, Interactive CAD Solutions.

“In the week after I got the app, I generated more than $20,000 in sales,” Conley says. On his business’ home page, Conley offers a downloadable PowerPoint deck with a bullet list of services. Augmented reality is on the very top of that list.

Conley belongs to a small but growing group of CAD users who see AR as a legitimate design and engineering tool, not a purposeless novelty. The adoption of augmented reality may be slow among small businesses with limited expenditure for experimentation. However, according to CCS Insight, an analyst firm that tracks mobile communication and Internet commerce, AR is “starting to gain traction in industrial and business arenas … Europe is currently the largest test bed for this technology, with numerous blue-chip companies across all sectors evaluating its capabilities.”

CCS Insight predicts devices powered by AR and its twin VR (virtual reality) could become a “$4 billion-plus business in three years.” With the promise of such real money, some hardware and software vendors are already shifting their R&D strategies and IP (intellectual property) acquisitions to cater to early adopters of AR and VR.

Augmented Reality to Go

For Conley, AR is more than showmanship and razzle-dazzle. Some parts are physically too big or bulky for him to haul to the client’s site during design reviews. For those, Conley used to rely on onsite measurements and some educated guesses to determine how the designed part would fit into the client’s facility or existing machinery setup. These days, he uses his business card as the digital replica of the new part.

“My two-fold business card has a global marker for [the] eDrawings iPad app,” he said. “I just put down my card where the part was supposed to go, and check interferences.” The app recognizes the marker as the placeholder for a specific digital model; therefore, through the tablet’s camera view, the app projects the digital part into the real world. Through XYZ coordinates, the digital part’s orientation is aligned to match the physical environment where the marker sits.

In early experiments with eDrawings’ AR tools, Conley learned a valuable lesson about the computer-recognizable markers. “When I printed the global marker on my card the first time, I shrank it to fit the card,” he recalled. That, he found out, caused his digital model to appear in a smaller scale in the app’s window.

Being portable and lightweight, the tablet offers a tremendous advantage to Conley. It allows him to deploy AR at any given location. On the other hand, the device’s limited memory capacity proves to be a current drawback. “One of the biggest challenges is working with large models,” says Conley. “I haven’t found a way to overcome that yet.”

eDrawings displays SolidWorks models and industry standard neutral 3D formats (such as STEP or STL). But sometimes the clients give Conley files that are not supported by eDrawings. Conley’s solution is to use GrabCAD Workbench, an online collaboration platform, to convert them to the right file format.

The Heart Beats Faster in Stereo

At the NAFEMS World Congress in June, Steve Levine, Dassault Systemes’ SIMULIA chief strategy officer, stood in an exhibit booth with a pair of stereoscope glasses dangling on his nose. He invited visitors to dissect a virtual heart, known as the Living Heart Project, loaded into the zSpace virtual reality display as a 3D model.

According to Levine, what stereoscopy offers is a sense of scale and the ability to experiment without jeopardizing a real patient. “If you show surgeons a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model or a finite element analysis (FEA) model, they have a tough time grasping it,” he said. “But if you show them this, they got it instantly. They’d take the heart apart, look at its cross-sections, and talk about how they might have operated on a particular patient’s heart.”

Dassault Systemes, a 3D software powerhouse, is betting heavily on the notion that, in the future, consumers will want to pay for experiences (a combination of hardware, software, apps and services); therefore offering them products alone will no longer be sufficient. Life sciences is one of the new markets the company is actively courting. Levine and his colleagues recognize a high-end CAD program like CATIA would be more an obstacle than a tool for the surgeons and medical professionals. The learning curve alone would be discouraging to those who are outside the engineering and design disciplines. The Living Heart on zSpace is a tailor-made solution, comprising a detailed 3D heart model loaded on a portable stereoscopic tablet with virtual cutting tools. It’s the type of offering that can help Dassault Systemes break into new markets beyond traditional manufacturing.

Researchers may use Dassault Systemes’ 3DEXCITE technology to view an accurate heart model inside a virtual cave environment. Image courtesy of Dassault Systemes.

Researchers may use Dassault Systemes’ 3DEXCITE technology to view an accurate heart model inside a virtual cave environment. Image courtesy of Dassault Systemes.From Entertainment to Engineering

“VR is one of the most exciting things to happen to CG in the last decade,” says Vladimir Koylazov, co-founder and lead developer for V-Ray rendering software at Chaos Group. He and his colleagues are laying the groundwork for the era of stereoscope VR content. In June, the company announced the release of V-Ray 3.2 for 3ds Max, a free upgrade that includes two new VR camera types to “render stereo cube maps and spherical stereo images for VR headsets such as Oculus Rift and Samsung Gear VR.”

The technology offers a more in-depth look and added element of interactivity that traditional designs may not. “With VR, you can make informed decisions about whether something would work correctly,” says Lon Grohs, chief commercial officer at Chaos Group. “Virtual prototypes in VR are so much more realistic than what people have seen before. I could inspect the virtual prototype as if it were the real thing, before the real thing is available.”

Additionally, stereoscopic content offers a sense of scale, a critical factor in all engineering judgments. “If you walk into a VR atrium, it’s far closer to walking into the real atrium than you would feel with another medium. If you’re designing a car, for example, you’d be able to judge if the door handles are in the right places,” says Christopher Nichols, creative director at Chaos Group.

You can explore VR environments in regular flat panel displays, using the mouse and keyboard for path finding. However, experiencing VR content through immersive devices like the Oculus Rift or Samsung Gear VR gives you a more natural way to interact with the environment, also a better understanding of the volumes and distances represented by the 3D models.

Using VR for product development, however, adds a greater burden on the content creator, the one who produces the digital prototype or environment that will be uploaded to the VR goggles. The dimensions of the objects in the VR world have to be geometrically precise, not approximations (as they might be in VR-powered videogames and movies).

Currently, there’s no straightforward way to create VR content in CAD software; therefore, VR content will most likely be created by importing CAD-authored 3D content into rendering programs like 3dx Max or Maya.

For the novice VR content creators, Nichols offered a tip. “You have to pay attention to the intraocular distance [the distance between the virtual observer’s eyes, represented by the distance between the two cameras in a stereoscopic rendering program]. Getting that distance wrong is like shrinking or expanding the [virtual observer’s] head. If that distance is too big, then the world looks a lot smaller; if it’s too small, the world looks too big,” he says.

Cognitive Computing Coming Up

“We’re moving from cloud computing to cloud, mobile and wearable computing—the convergence of the three,” said Ahmed Noor, a scholar from Old Dominion University, as part of his keynote speech at the NAFEMS World Congress 2015.

He envisioned a future where designers and engineers might work with “cognitive systems that mimic the way humans work through natural language processing, data mining and pattern recognition.” This, according to Noor, is the precursor to the next phase, “anticipatory computing, in which cyber-physical systems can recognize the user’s needs by watching the user, and provide them with tools without being asked.” Whereas today’s human-machine interaction is limited to robotics and software, Noor thinks we will eventually interact with “multi-model virtual holography.”Some groundwork for Noor’s vision may already be on the way. This April, Vuzix Corporation, which supplies video eyewear and smart glasses, snatched up U.S. Patent numbers 6243054 and 6559813 for an undisclosed sum.

“Gesture control with AR applications and managing the ambient light, especially in optical see-through glasses, is critical in the operation of wearable display technology and especially augmented reality in smart glasses. Vuzix acquired these additional patents to secure a stronger IP position for its current and soon to be released products,” says Paul Travers, CEO of Vuzix, in his explanation of the IP acquisition.

According to the patent office’s public records, Patent 6243054 is described as “a computer system [that] stereoscopically projects a three dimensional object having an interface image in a space observable by a user. The user controls the movement of a physical object within the space while observing both the three dimensionally projected object and the physical object.”

Patent 6559813 is “a virtual reality system [that] stereoscopically projects VR images, including a three dimensional image having an interface image in a space observable by a user. The display system includes a substantially transparent display means, which also allows real images of real objects to be combined or superimposed with the virtual reality images.” Both patents promise “a way to contact user interface images without contacting a keyboard or a mouse or the display itself.”

zSpace’s display tablet with stereoscopic glasses and virtual cutting tools allow those outside engineering and manufacturing to interact with 3D technology. Image courtesy of zSpace.

zSpace’s display tablet with stereoscopic glasses and virtual cutting tools allow those outside engineering and manufacturing to interact with 3D technology. Image courtesy of zSpace.Rethinking the Human-Machine Interface

Finding the prevalent terms AR and VR inadequate to describe its new product HP Sprout, HP introduced another term—blended reality (BR). At its core, HP Sprout may be an all-in-one multi-touch computer, but the mounted projector and a camera, a paper-like surface for projection and sensors offer multiple methods of interacting and capturing content, both in 2D and 3D.

The emerging AR, VR and— to borrow HP’s vocabulary—BR devices will likely colonize the general consumer market and entertainment industry before they find acceptance in the more conservative engineering market. But when they do, design and engineering software vendors may confront one of their biggest challenges. Adapting legacy CAD software code that relies on the mouse and keyboard to a new breed of portable, wearable, head-mountable computers that invite touch, natural speech, and gesture input won’t be easy.

More Info

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE