Latest News

June 4, 2010

On Saturday May 22, as midday approached at Maker Faire Bay Area, I was frantically trying to reach Paul Grayson, CEO of Alibre. It was 30 minutes past our appointment. He was somewhere in that swelling tide of people (estimated 90,000), rolling through 48 acres of fairground. His PR firm has provided me with his cell phone number and his booth number, but neither was of much help. When I got a hold of him on the phone, his voice was drowned out by the sound of whirling gadgets and buzzing electronics. The map that came with the show guide didn’t include booth numbers. I was about to give up when I stumbled on him in the press room, giving an interview to a reporter.

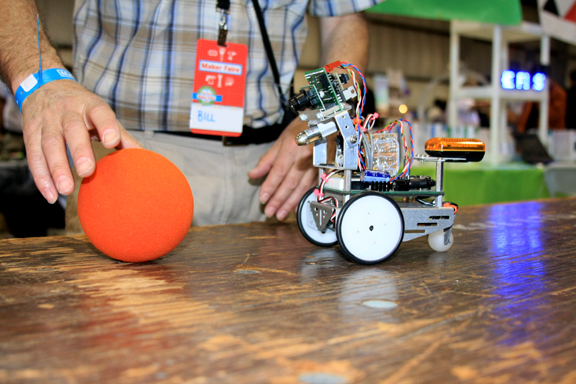

Maker Faire, an annual event organized by the editors of Make magazine (“Makezine” for those in the know), attracts the do-it-yourself types with a knack for arts, crafts, and science. Know how to put together an autonomous robot that tosses balls? Want to learn how to turn your old cigar box into a mandolin? Have a solely-for-pleasure engineering project you want to showcase? This is where you might come to teach, learn, or share.

The maker-tinkerer phenomenon, one of the cornerstones of American entrepreneurship, is as old as the country itself. It gave us Alexander Graham Bell, Henry Ford, Steve Jobs, and Bill Gates, among others. What’s new is the fast-growing maker communities, fueled by the rise of social media and the plunging cost of technology.

For engineering software developers like Grayson, this is a new field of opportunity, with plenty or unclaimed pastures and prairies. With a 3D modeling package selling for $99 (less than the price of an iPod Nano), Grayson believes his product has an advantage over Autodesk, SolidWorks, and other big names among this exploratory, hobbyist crowd. That’s why the six-foot-tall Texan (one of the few donning a dark suit at the fair) is marching down the aisles, rubbing shoulders with DJs who transformed their music into psychedelic colors, a Burning Man crowd that reprised their pyrotechnic centipede, and a composer who automated a traditional Indonesian orchestra (the contraption is dubbed The Gamelatron).

Personal CAD

Two days before he flew down to California for the fair, Grayson had his PR people issue an announcement. “Alibre announces Alibre Personal Edition, for entrepreneurs and inventors at Maker Faire.” It’s meant as “an industrial-strength, parametric solid modeling system with integrated 3D solid modeling, part and assembly design, associative 2D drafting, and STL export, all at a hobby-friendly price.”

“We want to make it possible for ordinary humans to make things,” proclaimed Grayson. “And that’s really what Maker Faire is all about. Of course, we’re focused on a particular type of things—mechanical products that’s precise, need to be manufactured.”

People who routinely use CAD programs are no stranger to Alibre. Last year, Grayson stirred the engineering software community by slashing its software’s price from $999 to $99. The Personal Edition is what Alibre has been selling for $99 first, later for $97, then back again for $99.

So why negotiate the $3 difference? Grayson admitted, “I’m kind of a crazy marketing guy at heart. I try things. Sometimes my own staff get mad at me because I keep changing it. But it’s part of my nature to want to try new things, experiment, and see how people would react to it.”

In the past, average people couldn’t afford to cut, finish, and assemble their own custom robots, because manufacturing facilities weren’t (they still aren’t) designed to cater to tinkerers looking for a low-volume production run. But today, with an affordable 3D modeling package, you could export your design as an STL file and print it (yes, print it in 3D) at a service bureau. The same workflow has spawned a viable industry revolving around printing customized avatars (from such online games as World of Warcraft or Second Life).

Personal Workshop

Perhaps you have heard of Zipcar, the company that lets subscribers pick up and use vehicles from a pool of cars for a low daily rate (for San Francisco, the advertised rate is $73 for weekdays, $88 for weekends, or $7 per hour). Gas and insurance are included in the plan. It’s ideal for those who must drive occasionally, but don’t have to (or don’t want to) own a car.

TechShop is the workshop equivalent of Zipcar. Would you ever need to own a laser cutter, a metal welder, or a milling machine? For most, the answer is, “Probably not.” But sometimes, when inspiration strikes, you might want to churn out a pair of laser-engraved earrings or a welded sculpture. For roughly $125 a month, TechShop allows its members to use its 15,200 sq. ft. facility, equipped with grinders, vinyl cutters, sewing machines, chop saws, band saws, 3D printers, and computer workstations. (Fresh brew coffee, pop corn, and WiFi also come with access to the place.)

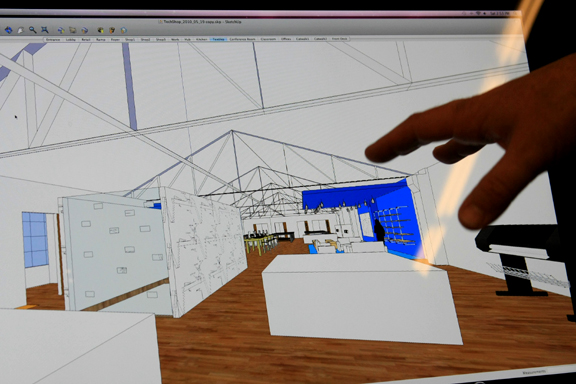

Something else you get at TechShop: CAD training (for additional fee, not part of membership). On July 6, for example, you can begin a 9-hour SolidWorks course (3 hours a week), to learn not just how to model but also to export your design to be produced in 3D printers, laser cutters, and mills onsite. If you have more time to spare, you can also take classes on mold making, fabrication, soldering, and basic electronics, all under the same roof where you might later put those skills to use.

Currently, TechShop has two locations: Menlo Park, California; Durham, North Carolina. But more shops are set to appear in San Francisco, San Jose, Portland, and beyond.

Tinkerers Wanted“None of this stuff was available to the amateurs 10 years ago,” said TechShop’s founder Jim Newton, waving at the hardware he’d brought along to Maker Faire. “Our members like instant gratification. They want to get something done. It may not be a long-term thing they want to do. So a software like [Autodesk] Inventor is particularly good for that.” With this crowd, a complicated software that takes months to learn just won’t cut it.

“Something interesting tends to happen with TechShop members,” noted Newton. “Somebody would have an idea for a product. They’d make 50-100 units. Then they can put it on eBay and sell it. We’ve had lots of people who spin off a business that way.”

The maker movement is a surging force, driven by personal creativity and the desire to produce something tangible. The outcomes range from mildly amusing, wildly impractical, to possibly market-ready. This is also unfamiliar territory for professional software makers. Whereas CATIA, NX, and Pro/E may carry more weight over smaller brands in automotive and aerospace, should they choose to compete for attention at Maker Faire, they’ll probably need to compete on equal terms with Alibre and the rest.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE