The End of TechShop: a Huge Loss to the Makers and DIY Community

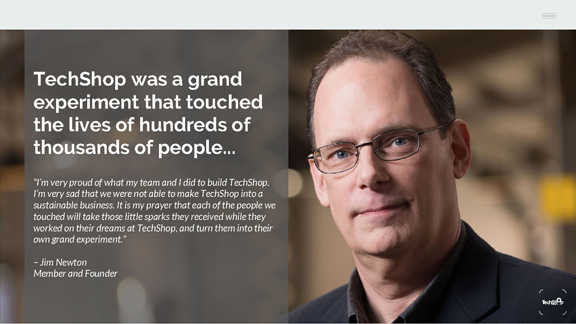

In its closing message to members, TEchShop founder Jim Newton wrote, “It is my prayer that each of the people we touched will take those little sparks they received while they worked on their dreams at TechShop, and turn them into their own grand experiment.”

Latest News

November 21, 2017

In its closing message to members, TechShop founder Jim Newton wrote, “It is my prayer that each of the people we touched will take those little sparks they received while they worked on their dreams at TechShop, and turn them into their own grand experiment.”

In its closing message to members, TechShop founder Jim Newton wrote, “It is my prayer that each of the people we touched will take those little sparks they received while they worked on their dreams at TechShop, and turn them into their own grand experiment.”When TechShop got ready to open its San Francisco branch in 2010, I visited the venue, still under construction back then. I met with TechShop’s then CEO Mark Hatch and founder Jim Newton in their new 17,000 sq. ft. facility, partially filled with half-assembled CNC machines and laser cutters. The shop floor didn’t feel empty; it was full of hope and promises.

Hatch and Newton felt, with their membership-supported mini-factory model, they had started a revolution in small-scale manufacturing, providing a much needed service to the DIY community.

“We are in the beginning of the largest creativity innovation the world has ever seen, driven by extremely powerful tools [CAD software] that allow you to visualize things before you make them,” said Hatch. “With TechShop capabilities, you can produce [your prototypes] in days, not months or years. Combine that with the long tail of the internet, you get friction-free ability to market things—we’re in a new space.”

This week, eleven years after its debut in 2006, TechShop announced it was closing its doors to all U.S. locations and filing bankruptcy.

TechShop’s homepage, once populated with CAD software class schedules and member success stories, is now a PDF farewell note, titled “closed for business.” In it, the company explains:

In spite of many months of effort to restructure the company’s debt and raise new capital to fund our recently announced strategic pivot, we have depleted our funds. We are left with no other options. We’ve worked with members, partners, and investors to try to turn the ship around. This meant slashing corporate spending, executive pay, and introducing an entirely new business model. But, in the final analysis, it wasn’t enough. It didn’t work.

The TechShop experiment left its indelible mark on the DIY community, but it also reveals the double-edged nature of startup success and serves as a reality check on the maker movement.

In its closing message, TechShop CEO Dan Woods wrote, “As a veteran myself, I’m proud to say that TechShop has provided membership and training to over three thousand returning veterans.”

In its closing message, TechShop CEO Dan Woods wrote, “As a veteran myself, I’m proud to say that TechShop has provided membership and training to over three thousand returning veterans.”Success and Expansion

TechShop began as a single location in Menlo Park. Over the next ten years, it grew into a chain of ten U.S.-based work spaces for tinkering, prototyping, low-volume manufacturing, and design exploration. It secured partnerships from Ford in 2010, and from the Veterans Affairs Office and DARPA in 2012. In 2011, TechShop began offering Autodesk software classes in partnership with the design software maker.

In 2014, TechShop participated in a special Maker Faire organized at The White House, part of the Obama administration’s efforts to “celebrate all things built-by-hand and designed-by-ingenuity,” and highlight the role of “3D printers, laser-cutters, easy-to-use design software, and desktop machine tools.”

The story of Mark Roth, a TechShop member who used the skills he learned at the work space to combat homelessness, exemplified the social impact of the company.

It was also the birth place of several products that, in their own ways, improve people’s lives around the world. The Embrace infant warmer, a newborn incubation blanket that reduces infant mortality risk, was prototyped in TechShop’ San Francisco location. The fashionable Lumio foldable lamp was funded on Kickstarter. Its inventor Max Gunawan was a TechShop member.

The Kickstarter-funded Lumio folding lamp was born in a TechShop facility.

The Kickstarter-funded Lumio folding lamp was born in a TechShop facility.Business Model Shift

This May, TechShop announced a fundamental change in its business model, signalling a move toward licensing rather than owning work spaces. Its press releases, published by Make magazine, said, “The licensing and managed services strategy will allow us to co-develop new locations with strategic partners—corporations, universities, municipalities, real estate developers—and rapidly grow a network of stores across the country.”

The change was one way they company tried to cope with the mounting challenges to maintain the existing chain of work spaces. At the same time, it also closed its Pittsburgh location. This, said the company’s CEO Dan Woods, was one of the difficult decisions he had to make “to get the total enterprise on a firm footing, financially viable, and capable of long-term sustainable operation.”

“Running maker spaces is a challenging endeavor,” said Jessica Muise, Artisan’s Asylum‘s Member Services & Outreach Manager. “We continue to believe that its viable for maker spaces to continue to provide not just tools and facilities but creating a space for thriving communities. We’re always disappointed to see people lose access to resources that help them make their vision a reality.”

Based in Somerville, Massachusetts, Artisan’s Asylum is a nonprofit community workshop for teaching, learning and practice of fabrication.

In its final letter to members, TechShop CEO Dan Woods pointed out, “A for-profit network of wholly owned maker spaces is impossible to sustain without outside subsidy from cities, companies, and foundations, often in the form of memberships, training grants, and sponsored programs. This kind of funding is readily available to nonprofits, and very rarely an option for for-profit enterprises.”

The TechShop global locations are not affected by the U.S. company’s closure, as they are all owned by overseas licenses, TechShop clarified in its final message.

The Changing Landscape of Manufacturing

When TechShop debut in 2006, the cost of professional equipment was a prohibitive factor. Therefore, shared work spaces with access to industrial equipment for a nominal membership fee was an extremely attractive proposition. But since then, the prices of 3D printers, laser cutters, and desktop milling machines have significantly dropped.

XYZ Printing’s da Vinci Color, set to ship this month, is priced $3,499. Ultimaker 3, billed as a professional 3D printer, is priced $3,495. MakerBot’s professional printer Replicator+ is priced $3,499. These competitive prices dissolve some of the previous barriers to equipment ownership and low-volume production.

Furthermore, many emerging service bureaus and online part ordering portals now cater to those with low production runs—even to those who need single parts.

On-Demand Manufacturing

With a branch office in San Francisco, HAX describes itself as a hardware accelerator. HAX was the subject of a WIRED documentary titled “Shenzhen: The Silicon Valley of Hardware.”

“For small-scale manufacturing, local and foreign supply chains have opened up. Shenzhen, where HAX is based, has become a mecca of sorts even to make a single unit,” said Cyril Ebersweiler, one of the founders of HAX. “Serious makers might buy their own machines, or learn to order the parts they need if they can’t make them from services such as Plethora [a custom machining service provider].”

“[TechShop’s closure] is reflective of a larger struggle small fabrication shops experience in the U.S today. In a digital and globalized age, it’s incredibly difficult for small, local shops with limited capacity to compete with larger factories,” said Dave Evans, CEO of Fictiv, is an online manufacturing platform connecting machining services providers and manufacturers.

The software and equipment training offered by TechShop as part of its membership benefits also face stiff competition from peer learning, free resources, and vendor-sponsored workshops to cultivate new businesses.

“Peer learning is an exceptional resource for kids, hobbyists, and startups alike. In Shenzhen, HAX hosts over 200 hand-picked startup founders for that exact reason. While they are lots of makers around, many are learning and tinkering at home, without the need to educate themselves or go pro,” observed Ebersweiler. “TechShop’s closure says more about the maker pro movement (makers who have to professionalize on their own) than it does about the maker movement.”

The Void to Fill

TechShop’s closure left a void that might be filled by “maker spaces, both private and public, at universities or community colleges, for instance,” noted Ebersweiler.

“Community organizations like Hackster are empowering a generation of hackers and makers with educational information. Universities, nonprofits, and government bodies should step up to provide young innovators exposure to technology early on,” said Evans. “I also believe it’s crucial to strengthen small, local fabrication shops by bringing them online and introducing automated systems to decrease overhead costs and increase efficiencies ...”

Artisan’s Asylum has a resource page dedicated to creating and running maker spaces. “Our staff can help guide you through the many steps involved in starting and running a makerspace, including equipment selection, safety, infrastructure and more,” the team wrote.

Life After TechShop

TechShop offered more than access to equipment, software training, and work space. The community spirit it spawned, the inspiration it fostered, and the camaraderie among its members were the intangible qualities that make TechShop’s closure a huge loss to the maker world.

Some former TechShop members have come together to save that spirit. After news broke that the Pittsburgh TechShop location was set to close, some of its members formed a local nonprofit group called Protoheaven in an effort to revive the work space under a different model.

In its video pitch to recruit founding members and solicit sponsorship, one Protoheaven founding member remarked, “We’ve already seen the goods a place like that can do to education, job training, and innovation.” Another one remarked, “It allows for an exchange or ideas you wouldn’t otherwise get.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE