Close-up of a long board with AM-specific wheel-holding bridges. Image courtesy of Autodesk.

Latest in Computer–aided Design CAD

Computer–aided Design CAD Resources

Autodesk

PTC

Latest News

April 15, 2021

As the phrase design for additive manufacturing (DfAM) has gained prominence in the engineering lexicon, traditional 3D CAD programs have been forced to reckon with an uncomfortable truth.

With standard commands such as Extrude, Revolve and Trim, parametric CAD programs’ fundamental architecture is rooted in subtractive manufacturing, a production method that relies on removing materials. AM, by contrast, produces parts by depositing layers of materials—the reverse of subtractive manufacturing.

When affordable 3D printers hit the market, design engineers realized the new breed of hardware could build shapes previously deemed impossible or impractical for consideration. Thus, the mad scramble to develop geometry modeling tools to match the capability of 3D printing began. Some now wonder: does DfAM demand a new breed of CAD? To answer, we spoke to the software and hardware developers on the front lines.

Classic With A New Twist

Though admitting most parametric CAD modelers come up short in tools for sculpting AM-optimized geometry, developers also gave forceful arguments against completely writing off classic CAD programs. Perhaps the most compelling reason to continue working with parametric CAD is the need to support subtractive and additive designs for the foreseeable future.

“A lot of our customers are adding additive parts to their existing designs. They’re not starting from scratch. So, you need the interplay between the two approaches,” says Brian Thompson, vice president and general manager of CAD, PTC.

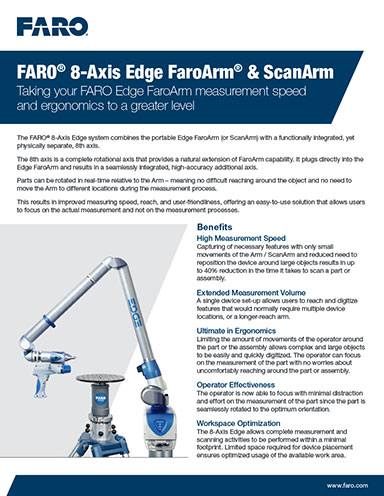

PTC integrates AM tools into their existing flagship modeling programs. Image courtesy of PTC.

“Aside from things like medical implants that are fully 3D printed, there will be very few discrete manufacturing products like tractors and engines where the entire bill of materials is filled with AM components,” he adds.

The incorporation of AM parts is rapidly growing, driven by the desire to reduce complex assemblies into a handful of 3D-printed parts. Such assembly simplifications usually lead to tremendous cost savings in production as well as assembly.

According to GE Additive on its website, “In a new advanced turboprop engine, a dozen 3D-printed parts replace 855 components produced by multiple contractors … The impact of parts consolidation will grow as maximum part sizes and build rates increase in additive manufacturing.”

“I don’t think the AM software should be an independent software. Having independent software means having to train on a new platform, which increases the barrier of entry. The industry can make a platform that allows you to smoothly navigate between the two environments [additive and subtractive],” says Kevin Acker, senior research engineer, Manufacturing Industry Futures, Autodesk.

Parametric CAD programs are beginning to enable AM-optimized objects such as unit cells with variable thickness, meso structures and meta materials. Acker believes CAD vendors need to continue augmenting their existing offerings with these functions.

Ongoing Integration

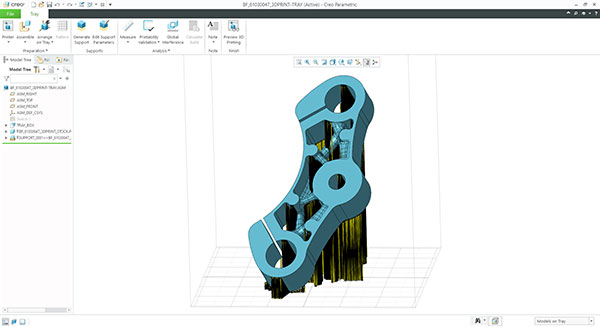

Two years ago, PTC acquired Frustum, the startup behind the AM-targeted modeling software Frustum Generate. PTC’s Creo Parametric CAD software can be augmented with an Additive Manufacturing Extension, which allows you to model AM-optimized lattice structures and manage print tray setup, among other tasks.

Autodesk Fusion 360, an integrated CAD/CAM/CAE program, includes parametric and direct modeling design tools for AM. It also offers integrated generative design tools, an algorithm-driven design method for generating complex structures for the desired manufacturing methods. Some print preparation and AM simulation tools from Autodesk Netfabb have been added to Fusion 360. PTC and Autodesk’s strategy exemplifies the integration of AM tools into their existing flagship modeling programs.

Algorithms vs. Manual

Though traditional parametric CAD programs serve as geometry sculpting tools that allow the user to produce the desired topology, offerings from AM-focused startups like Frustum and nTopology have shown that artificial intelligence-like algorithms will play a greater role in DfAM software. This has been the case as well with Autodesk’s incorporation of generative design tools in its Fusion 360 features.

“Because of the degrees of freedom possible with AM, it’s impractical to design the geometry manually. Most likely, it’s the computer algorithm designing it for you,” says Mike Grau, technical manager, Autodesk Research.

“Fewer parameters will drive more design decisions. Algorithms will play a greater role in AM design,” says David Busacker, senior engineering consultant, Stratasys.

CAD-integrated AM tools serve designers who are building products that, for the most part, will be produced using traditional manufacturing methods (machine, injection molding, sheet metal, etc.), but also incorporate 3D-printed components; however, for those looking to design products to be made entirely in AM, Busacker says “the software will likely be a different product than parametric CAD.”

In partnership with nTopology, Stratasys offers an FDM (fused deposition modeling) Fixture Generator, allowing users to easily generate the required fixtures and support structures for AM-specific parts. Such fixtures are a good example of parts impossible to model manually; they are generated based on AM- and hardware-specific rules.

“The design of these fixtures is not a common skill, so we just turn that into a program using hidden parameters,” says Busacker. In his view, this is just one type of AM-related microservices we can expect to see as DfAM adoption gains momentum.

Busacker also points to GrabCAD Print as another type of microservice—a simple app that allows a software user to interrogate the design for possible AM failures and get it printed. GrabCAD, a 3D modeling community and collaboration hub, was acquired by Stratasys in 2014.

New File Formats, New Methods

The standard 3D printing file format has been STL, a mesh-based 3D file format. But the quest for better file formats has led to the development of 3MF, a format spearheaded by the 3MF Consortium. Autodesk, GE, nTopology, PTC and Stratasys are all active members of this consortium.

“When it comes to lattices, you need a different infrastructure to mathematically define these. You might be able to create them in parametric CAD, but when you save the file, it might be a 30GB file that nobody can open,” warns Zach Murphree, vice president of sales, VELO3D.

Cut view of a redesigned version of the heat-exchanger using nTopology software to create complex gyroids that direct fluid flow to dissipate heat more effectively. With the auto-assignment of recipes found on VELO3D’s AM system, engineers can 3D print these complex designs. Image courtesy of nTopology.

VELO3D offers a print preparation software called Flow.

“Our software is specifically designed for our printers. It’s designed with the knowledge of our processes,” says Murphree. “It’s important to know the limitations of your manufacturing process as you’re designing, so when considering AM it would be helpful to have AM-specific tools in your parametric CAD program.”

As DfAM gradually replaces parts and assemblies previously made with subtractive methods, CAD vendors are expected to add more features and tools to address the void. This makes startups with robust AM-focused software offerings attractive acquisition targets for the CAD software titans. But for a large portion of the projects, subtractive methods remain the ideal solution, due to volume and cost considerations. Therefore, even if subtractive and additive are rival technologies, modeling software needs to evolve to accommodate both types of designs.

More Autodesk Coverage

More PTC Coverage

More Stratasys Coverage

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE