Metal 3D Printing with Stanley Black & Decker

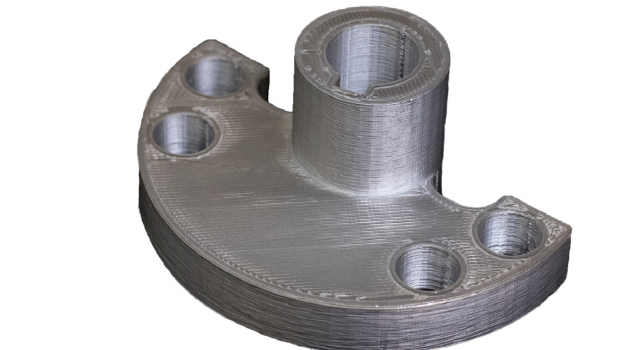

This metal flange printed on a Metal X 3D printer is a part of a wheel shaft assembly designed as an alternative to an original part that is inefficient in machine time and material costs to make. Image courtesy of Markforged Inc. and Stanley Infrastructure.

Latest News

March 8, 2018

Research can rock you. For example, while researching for today's Check it Out read, I was shocked to learn that LAPD Sergeant Joe Friday never said “just the facts, ma'am” while interviewing a crime witness in the old TV cop show “Dragnet.” But good research that lets you learn things that rock what you thought you knew were “just the facts” is a good thing. That kind of rocking good research is what we have today.

Technically speaking, “Metal 3D Printing with Stanley Black & Decker” from Markforged is a case study. Apparently the writer never got the memo. See, this short read is pretty much the definition of “just the facts” and not your typical warm and fuzzy word salad. It's also not techno-heavy, so the money handlers at your outfit will be able to read it and get valuable insights on the potential fiduciary benefits of 3D metal printing.

The story line is straightforward: An engineering team at Stanley Infrastructure, a division of Stanley Black & Decker, is checking out metal 3D printing using Markforged's new Metal X fabrication system. They want to learn if it proves to be a viable alternative to subtractive manufacturing for making complex components. Among the research drivers are cost-effectiveness in low volumes (sometimes as low as a single unit), cost reductions and shorter lead times.

This metal flange printed on a Metal X 3D printer is a part of a wheel shaft assembly designed as an alternative to an original part that is inefficient in machine time and material costs to make. Image courtesy of Markforged Inc. and Stanley Infrastructure.

This metal flange printed on a Metal X 3D printer is a part of a wheel shaft assembly designed as an alternative to an original part that is inefficient in machine time and material costs to make. Image courtesy of Markforged Inc. and Stanley Infrastructure.The parts they 3D printed were an actuator housing for a hydraulic post driver and a wheel shaft for a profile grinder used for surface finishing operations on railroad tracks. Each was redesigned to leverage the Metal X 3D printer's capabilities as well as off-the-shelf parts when applicable. They then beat on the 3D parts to determine if they could survive the stresses that the machined originals undergo.

This paper steps you through this process. Its formula is to introduce the original part and explain why it is deemed a candidate for 3D metal printing.

Then, using photos, annotated images and words, it compares the original design to the part's redesign for 3D printing fabrication. Testing is explained. Test results for the 3D part's physical performance are supplied. The paper compares the part's cost performance to the original part in percentages. Finally, there's a brief results analysis.

That's it. Just the facts, man. And that succinctness, coupled with good data, makes “Metal 3D Printing with Stanley Black & Decker” one of the stronger case studies going. Well done.

Thanks, Pal. – Lockwood

Anthony J. Lockwood

Editor at Large, DE

More Markforged Coverage

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Anthony J. Lockwood is Digital Engineering’s founding editor. He is now retired. Contact him via [email protected].

Follow DE