Latest News

Ansys Government Initiatives Picked to Join Microelectronics Commons

Simplify Simulation Data Analysis with Noesis Solutions Tool

Lantek Launches v44 of its Sheet Metal Manufacturing Software

Nano Dimension Unveils 3D Printer for Micro Applications

Prusa CORE One 3D Printer Serves as Foundation of New Line

Dassault Systèmes Announces Winners of India-Based Product Design Competition

All posts

May 25, 2007

By Mark Clarkson

For speed maven Russ Wicks, it’s an engineering team.

Russ Wicks likes to go fast. He was racing motocross professionally at 15. He’s piloted everything from Top Alcohol dragsters to Unlimited hydroplanes, and holds world speed records on both land and water. On July 3, 2006, Wicks’ Team American Challenge broke the world stock car speed record in a NASCAR-compliant Ford Taurus, thanks to a widely distributed team of desktop engineers and a bit of Autodesk software.

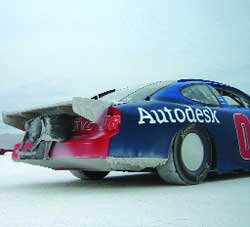

Wicks’ modified NASCAR Ford Taurus stock car posing on the Bonneville salt flats in Utah. |

“Team American Challenge is really an ‘engineering team’ as opposed to a ‘racing team,’” says Wicks. “Our core group consists of a couple aerodynamicists, a structural engineer, and a few other mechanical engineers.” And Wicks himself, of course, to drive.

“We don’t have one office,” says Wicks. “We’re really a virtual company, with

people all over. We use ]Autodesk] Streamline software for collaboration — design reviews and so on. It’s been amazingly valuable, from a communication standpoint, to speed up our process.”

What’s Next on the List?

Team American Challenge started off by breaking the speed record for propeller-driven boats. But that was in 2000; it was high time to go for a new record. The team is working on a jet-powered boat to go for the outright water speed record, but that vehicle will still be a little while in coming.

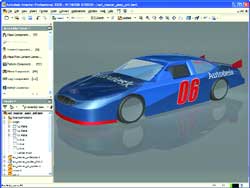

The Inventor model of Wicks’ record-breaking stock car, sporting an extra-legal rear spoiler. |

Fortunately, Wicks has a sort of to-do list of speed records in need of breaking. One of them was the World Stock Car Speed Record, set in 1971 by NASCAR champion driver Bobby Isaac.

It was a perfect project. A 35-year-old record in need of breaking, and one that could use an existing car, rather than one designed and built from scratch. The wild popularity of NASCAR didn’t hurt, either.

“The challenge,” says Wicks, “was to do it entirely within the NASCAR rules and regulations.” That meant no extra aerodynamics, no special tires … not even a driver’s side window, since NASCAR cars have a safety net instead.

“We purchased a Super Speedway car that had raced at Daytona,” says Wicks. “But even though that oval has fairly long straights, the car was basically designed to turn left. It wasn’t symmetrical at all. The body was not only offset to the left, it was angled to the left.”

The record attempt would take place at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, rather than a banked oval. For safety and speed reasons, Wicks wanted a car that would go straight: “The challenge was taking an existing vehicle meant for another application, and figuring out how to modify it to do what we wanted to do.”

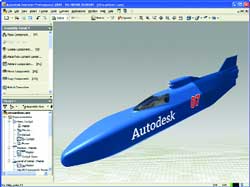

The team’s new 30-foot streamliner, complete with Wicks-sized humanoid, is a work in progress aimed at breaking the gasoline-powered world speed record of 364 mph. The team is hoping for 400 mph. |

Can You Scan Under Here, Please?

The project started with a complete, day-long 3D optical scan of the car, performed by Capture 3D in Costa Mesa, CA, capturing every detail of the car for every angle. “We even lifted the car up in the air and scanned underneath it,” says Wicks.

The resulting set of enormous STL files went to a team member in Germany, who cleaned them up using AliasStudio. The smaller, tidier models then went into Autodesk Inventor.

“Initially,” says Wicks, “our guys used Inventor as a measurement tool, to measure the differences from side to side. That gave us a good baseline for understanding how the car worked, how it turned left, and how to get it to go straight.”

There wasn’t time for wind-tunnel testing. To understand the airflow over the car at high speed, American Challenge partner Analytical Methods of Redmond, WA, provided a virtual wind tunnel for the Inventor model via CFD (computational fluid dynamics).

“Fun” in the Sun

The team’s four days at the Bonneville Salt Flats, July 1-4, quickly went from hectic to frantic. “The very first time we made a run,” says Wicks, “the engine blew up. Of course. So our guys had to travel thousands of miles for another engine — it was an all-night affair.”

The rear of the car with the new spoiler and a non-NASCAR standard braking apparatus. |

“The salt is such a different surface,” says Wicks. “It’s very, very challenging. And NASCAR uses big 10-inch wide slicks. From a driving perspective, that’s very difficult.” Even so, Wicks wanted to push the car further: “The guys had used Inventor to create a different rear spoiler and an aluminum belly pan that could quickly be bolted on to the car.” The team also added a plastic driver’s window and wheel covers, and changed to skinnier front tires.

On July 4, Wicks averaged 237 mph in the non-NASCAR configuration. “That’s really fast for one of those cars,” says Wicks. Very nearly too fast. “The bottom was completely enclosed,” Wicks recalls, “but we didn’t get a chance to seal the wheel wells. At 237 miles an hour, the air was packing up from the wheel wells, and buckling the hood so badly I could see the whole air cleaner. I’m surprised it didn’t blow off.”

Buckled hoods notwithstanding, Wicks was pleased. “Using Inventor, we were able to go out there with a car setup we felt really comfortable with, and break a record that was many years old on our first attempt.”

The entire project took six weeks, from the initial scan to the record-setting run. “None of our guys had ever used Inventor prior to this,” says Wicks. “It was a very quick learning experience.”

Gas-Powered Record

In addition to the jet-powered boat, American Challenge is currently designing a vehicle to attack the gasoline-powered world speed record: a 30-foot missile called a streamliner.”

“The current gasoline record is 364 miles an hour,” says Wicks. “Our hope is to round it up to 400.”

The streamliner’s design moved from napkin sketch directly into Inventor where Wicks’ distributed team of engineers labors over it even now, testing the driver’s line of site and the body’s aerodynamic efficiency long before they’ll actually build the thing. They are, after all, an engineering team.

“I never went to school to be an engineer but I’ve been around it since my teenage years, I’ve absorbed as much engineering as I can.” In fact, Wicks designed the wheels for the streamliner himself, in Inventor.

More Information

Russ Wicks Home Page

russwicks.com

russwicks.com

Contributing Editor Mark Clarkson, a.k.a. “the Wichita By-Lineman,” has been writing about all manner of computer stuff for years. An expert in computer animation and graphics, his newest book is “Photoshop Elements by Example.” Visit him on the web at markclarkson.com or send e-mail about this article here.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Join over 90,000 engineering professionals who get fresh engineering news as soon as it is published.

Latest News

Ansys Government Initiatives Picked to Join Microelectronics Commons

Simplify Simulation Data Analysis with Noesis Solutions Tool

Lantek Launches v44 of its Sheet Metal Manufacturing Software

Nano Dimension Unveils 3D Printer for Micro Applications

Prusa CORE One 3D Printer Serves as Foundation of New Line

Dassault Systèmes Announces Winners of India-Based Product Design Competition

All posts

About the Author

Mark ClarksonContributing Editor Mark Clarkson is Digital Engineering’s expert in visualization, computer animation, and graphics. His newest book is Photoshop Elements by Example. Visit him on the web at MarkClarkson.com or send e-mail about this article to [email protected].

Follow DE#9528

New & Noteworthy

New & Noteworthy: Future-Proof Foundation for Employee Training and Education

Eagle Point Software's Peak Experience for Pinnacle Series adds AI chat, improved...

Eliminate Physical Clamping – With Simulation

The Virtual Clamping tool in ANSA (VCA) from BETA CAE Systems eliminates...

New & Noteworthy: Fast, Flexible and Scalable Simulation – In the Cloud

Ansys Access on Microsoft Azure enables seamless deployment of industry-leading simulation tools...

New & Noteworthy: Safe, Cost-Effective Metal 3D Printing - Anywhere

Desktop Metal’s Studio System offers turnkey metal printing for prototypes and...