Latest News

March 9, 2011

Generally, the brand of Intel chip inside your machine gives you a pretty good way to determine which market segment it’s meant for. Got an Intel Core? That’s a home and business machine. Got an Intel Xeon? That’s a professional machine. But somewhere between those two classes, Intel and its partner OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) have added a new category: entry-level workstation.

For years, price-conscious buyers have been creating their own unauthorized workhorses. Often, they do it by purchasing a high-end home or business machine, adding a GPU, and bolstering its RAM. The downside of that, of course, is that they ended up with configurations that weren’t supported by professional software makers, particularly those who publish 3D design and engineering software.

Hardware makers like HP and Dell took notice too. And they decided to enable what they couldn’t stop, by creating the entry-level workstation category. Priced to appeal economy buyers but powered by Intel Xeon processors, these entry-level machines are certified for heavyweight CAD packages.

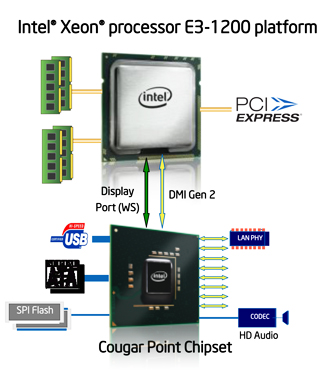

The new machines coming out the next season will most likely be powered by Intel Xeon E3-1200, the chipset series Intel has branded with 3 Ps: “Practical, Professional Workstation Performance.” Intel wrote, “These processors power entry-level workstations that merge the traditional strengths of the professional workstation with a new processor-based Intel HD graphics technology to tackle entry-level data analysis, CAD, digital animation, and 3D imaging challenges.”

Thor Sewell, director of Intel’s workstation business strategy, explained, “The new Intel Xeon processor’s greatest innovation is how it integrates—for the first time in entry workstation product—the CPU and graphics engines on the same die. That means visual and 3D graphics capabilities that were once only available to entry workstation users with discrete graphics cards will now be accessible to anyone with an entry workstation with Intel HD Graphics P3000. It changes the definition of the workstation and it may potentially change the form factors it is delivered in.”

Sewell pointed out that HD Graphics P3000 in Intel Xeon is not to be confused with the Intel HD graphics 3000 on Intel Core i7. “The P3000 is only available on Intel Xeon E3-based workstations and it delivers some amazing graphics performance for professional applications from SolidWorks, Autodesk, and ADOBE,” he distinguished the two.

Intel argues that putting the general processing unit and graphics processing unit on the same die—as it is the case with Xeon E3-1200—is a better approach than using a discrete graphics card, because the shorter passage (physical distance) between the two processing units cuts down on data travel, thus improves throughput.

Intel recently signed an agreement with NVIDIA, for a significant sum. “Under the transaction, Intel receives a license to NVIDIA’s patents subject to the terms of the agreement,” the announcement reads. “NVIDIA receives a license to Intel’s patents subject to the terms of the agreement, including that x86 and certain other products are not licensed to NVIDIA under the agreement. Intel and NVIDIA have also exchanged broad releases for all legal claims, including any claims of breach of their previous license agreement. Intel will pay NVIDIA $1.5 billion over the next 5 years.”

The agreement also ends the legal battle between the two. In their words, they “resolved pending litigation in Chancery Court in Wilmington, Del., ending all outstanding legal disputes between the companies.”

It’s unclear how exactly Intel plans to use chunks of NVIDIA technologies it now has access to. Intel is rather tight-lipped about it. And the end of their legal feud hardly means the end of their market rivalry. If anything, this might be a case of coopetition—competitors working together for mutual gain in an area where their interests happen to merge.

In this case, that coveted area is graphics acceleration.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DERelated Topics