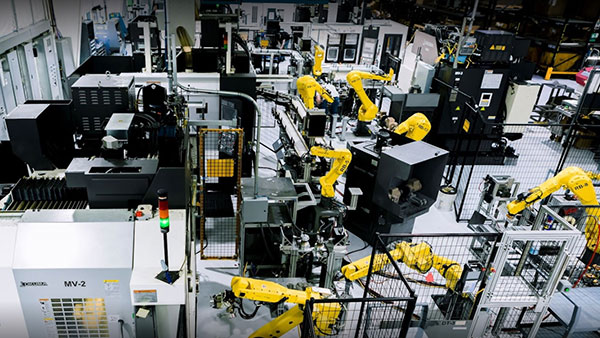

MetalQuest is a Nebraska-based custom manufacturer that uses digital twin technology to automate processes, stay competitive and cope with a tight job market. Image courtesy of MetalQuest.

Latest News

December 21, 2022

In early 2022, a global candy manufacturer decided it was time to upgrade shelf materials for its various chocolates. Five years ago the process was well understood. Traditionally, they would spec a material, draw a design, create a physical prototype—and then repeat, over and over. This time, the candy company took a different path. It designed a 3D model using digital material data, then subjected the model to simulation. Instead of 100 physical tests over various design iterations, they now do two, at the tail end of the engineering process.

Such stories are becoming more common as, one by one, manufacturers embrace various aspects of the design data revolution. Several drivers are pushing this transition. Some are macroeconomic factors such as global supply chain issues, inflation and a shrinking talent base. Others are more internal, like the need to decrease production costs. There are also societal pressures, primarily the demand for products and packaging that are more environmentally friendly.

All of this means increased complexity. Aerospace and automotive Tier 1 companies may have huge budgets to upgrade engineering processes, but it is a different story for engineering-driven small and medium enterprises. An example out of Nebraska—not traditionally viewed as a manufacturing powerhouse in the U.S.—offers glimpses of the way forward.

MetalQuest is a custom manufacturer of tight tolerance, precision-machined components. Its customer base is primarily in oil & gas extraction and agriculture, with the occasional aerospace job. In recent years MetalQuest has upgraded its manufacturing centers in Nebraska and Idaho with computer-driven multi-tasking lathes, identification tags for all raw materials and computer vision inspection.

Nebraska currently has an unemployment rate below 3%—second lowest in the U.S. MetalQuest struggles to hire new talent, even when working with a regional vocational college. So they look to automate wherever possible and use technology to augment the capabilities of each employee.

MetalQuest management has identified three business drivers as crucial, one in engineering and two in manufacturing. The first is to reduce the time it takes to complete a request for quote (RFQ), the initial document in any new project. RFQs are becoming more complex, which means more upfront engineering design. Second, the company wants to reduce work cell design, required by its increased reliance on advanced machining centers. Third, MetalQuest wants to minimize non-value-add shop floor processes, primarily rework.

The company standardized on SolidWorks years ago, and is now extending into more of the portfolio from parent company Dassault Systèmes for passing data not only between software applications but also to machining.

“It was a ‘Star Trek’ moment to see the ability to program multiple robots with one system,” notes Lynette Frey, an instructor at Southeast Community College in Nebraska and a consultant for MetalQuest. “You only have to train a person to use one system.”

Wither the Digital Twin and Thread?

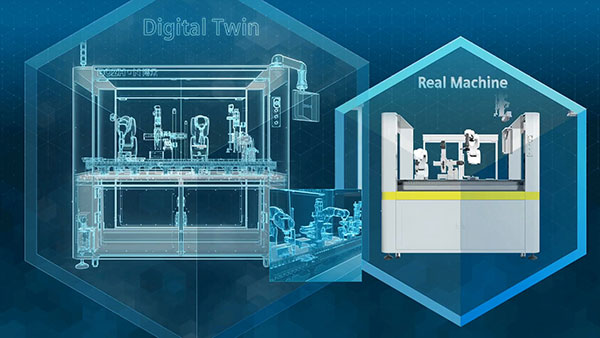

The technology MetalQuest is adopting is commonly called a digital twin and digital thread (also known as DT2.) The twin is the model of all data—not just geometry. The thread is when data can be passed from engineering to manufacturing without translation or rework. Most engineering technology companies embrace the DT2 paradigm and offer various implementation methods.

Despite good intentions and sophisticated technology, many engineering teams are working backwards. They create a digital twin as a record after manufacturing. Or they craft a separate simulation model but don’t have a direct connection to a physical device.

Facebook Horizon is one of several 3D metaverse environments that encourage users to become virtual makers. Image courtesy of Meta.

One of the purposes of this DT2 paradigm is to provide a direct, digital feedback loop. Information transfer should not be one way and linear. This is especially true when the various bill of materials (BOM) descriptions are added to the mix.

Under the traditional system, the engineering, manufacturing and service BOMs were separate documents with three distinct workflows. In a DT2 BOM workflow, all three can contribute elements to the others. This requires an initial level of granularity in all three, but the payoff comes as the data can be used and reused as is.

Beyond internal workflow, a service BOM as a digital twin can track product use and serial numbers of replaced parts. The goal is to have a constantly updated single source not only for engineers and manufacturers but also for service technicians.

As detailed in a recent Digital Engineering article on the metaverse [digitalengineering247.com/r/27073], the next frontier for the DT2 paradigm is to become a live agent, which some are calling the live digital twin. Some will call it the metaverse, or cyberspace, but for manufacturing it is simply two new elements: the increased availability of engineering data as models and the addition of real-time input.

In a live digital twin environment, the most common interface will be a flat screen. We won’t all need to be donning special headsets just to see the data. Live digital twins mean what we now call a dashboard becomes available as a 3D display and as textual data, whatever works best. Not only is data available in 3D, but it is delivered in real time. Is there a change order? In the live digital twin, engineers can see how it progresses even before a release is sent.

Many engineering software vendors are embracing digital twin technology to support expanded use cases for real-time engineering and manufacturing tracking and feedback. Image courtesy of Siemens Simcenter.

Each engineering team will have to work out the peculiarities of how it implements live digital twin technology. Some prefer the “one throat to choke” model of getting everything from the same vendor; others want to pick and choose their tools.

Young engineers now entering the workflow don’t think of live digital twin technology as exotic or complicated; they are already using it. They know it as one or more existing immersive platforms that display models and related data in real time. They don’t know it as PTC or Siemens or Autodesk, they know it as Fortnite or Roblox or Zepeto or Facebook Horizon. If you are fortunate enough to hire one of these new graduates, they won’t see your emerging digital twin as new, just an upgrade.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Randall S. Newton is principal analyst at Consilia Vektor, covering engineering technology. He has been part of the computer graphics industry in a variety of roles since 1985.

Follow DE