Latest News

December 3, 2010

On Tuesday November 30, as I made my way through the maze of slot machines and roulette tables in Mandalay Bay to get to Autodesk University (Nov. 28 - Dec. 2), I carried my trusty Canon PowerShot with me. Loaded with a 4GB memory card, the portable camera would let me shoot about 1,600 photos at 300 dpi. At this rate, I don’t need to worry about inadvertently taking a few dozens of, or even hundreds of, imperfect shots.

But it wasn’t that long ago that we were confined to 12, 24, or 36 exposures. With a finite number of shots in each film strip, we constantly monitored the remaining number and used them frugally. We couldn’t afford to take too many bad or mediocre shots. We had to make every shot count. Today, with digital cameras providing seemingly infinite capacity, we take photos with a different attitude. We say, “Shoot now, choose later.” We shoot on a whim. Even if we’re unskilled, we can be confident that one out of every ten will turn out well. The numbers are in our favor.

Now, at conferences, I snap photos of not only what I need for articles and blog posts but also the unplanned moments I’m lucky enough to witness, like Autodesk CEO Carl Bass trying out a stereoscope goggle in an exhibit booth. (I also take photos of slides when I’m too lazy to take notes.) This gives me more opportunities to photograph what I might otherwise forgo and discover what I might otherwise miss.

What if you can treat computing power much in the same way you now treat digital photography? What if high-performance computing (HPC) becomes so widespread and affordable that you can deploy it on a whim? What would you render if you don’t need to wait two to six hours to produce an image? What would you study if your CPU won’t crawl to a standstill with every session of finite element analysis?

The Era of Infinite Computing, as Carl Bass calls it, is on the way. But many of us don’t yet possess the right mindset to take full advantage of it.

A Change in Mindset

In his opening keynote, Autodesk CTO Jeff Kowalski invoked the spirit of Albert Einstein with a quote: “You cannot solve a problem with the same mindset that created it.”

Up to now, we have been using computing power sparingly, for good reason. We’re confined to what we own. Short of buying another machine, we can’t get more horsepower than the maximum output of the processor in our desktop or laptop. But what if near-infinite computing power is available upon request?

Kowalski pointed out, “We don’t have to own all the computing power ourselves; we just have to [be able to] get to it.”

A good place to take a peek at Autodesk’s strategies for its future is Autodesk Labs, a public site where the company previews many of its R&D projects and let early adopters try them out. Many of the technology previews available here contains clues to how Autodesk plans to facilitate on-demand computing power.

For example, Project Photofly and its accompanying application Photo Scene Editor let you upload a series of digital photos (roughly 36) of an object taken at slightly different angles to automatically extrapolate and construct a 3D scene from the source images. The technology provides engineers and designers with an easy way to capture the as-built geometry of an object (say, a cellphone), then import it into a CAD program for designing custom-fitted components (a cellphone cover, as the case may be). Custom prosthesis makers may use the same method to obtain the shape of a patient’s limb to design an artificial replacement.

You run Photo Scene Editor (downloadable from Autodesk Labs) from your desktop or laptop, but the heaviest of computing—algorithmically analyzing similar shapes and geometry in your uploaded photos and translating them into points in 3D space—takes place on a remote server. This setup allows you to continue to work on your local machine while the photo-to-scene conversion is taking place in the cloud. Currently, Photo Scene Editor lets you export the resulting 3D object as points (DWG) or scene (FBX). But in an upcoming release, Autodesk plans to let you export a mesh model.

Once a technology preview at Autodesk Labs, Inventor Optimization function is now poised to become part of the next release of Autodesk Inventor. (When it was in preview phase, it was codenamed Project Centaur.) The feature lets Inventor users specify certain parameters (expected load, thickness, material strength, and so on), then let the software automatically seek a the best design alternative. Like Photofly, the optimization also uses a cloud-hosted server to run the algorithms on submitted design files.

Soon, Autodesk 3ds Max users are also expected to be able to render their scenes by tapping into a cloud-hosted GPU cluster. The feature is powered by mental images’ iray rendering engine. Demonstrating this feature at NVIDIA GPU Technology Conference 2010, Autodesk used a remote GPU cluster built with NVIDIA Tesla cards.

In all examples, a desktop program serves as a client to communicate, request computing service from a remote cluster (or clusters, as the case may be), and retrieve the results. Autodesk is not yet revealing how it plans to bill customers for such additional services.

Not About Bigger, Faster Design

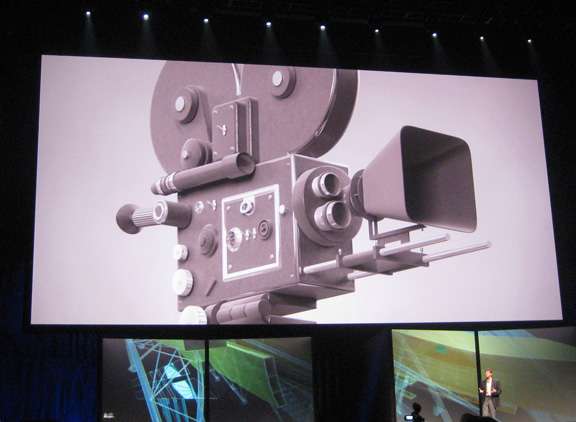

It would not be the wisest use of infinite computing if we simply think of it as a means to increase our design in scale: Design bigger, render larger, and so on. That would be the equivalent of the way early movie makers used—or misused—the additional possibilities offered by the invention of the movie camera.

“What they did,” explained Kowalski, “was simply planting a camera in front of a stage and recording plays that were already successful. Even the name they chose, Photoplay, shows how they perpetuated the old mindset using the new tool set. The real breakthrough only came when we began to look at the [movie] camera as a way to do something new, not as a new way to do something old.”

Remote access to infinite computing and storage means you can now use relatively lightweight devices, such as an iPhone or iPad, to interact with complex design files. It also bypasses the need for software-and-OS compatibility. Case in point: AutoCAD WS, now available at Apple app store, lets you use a mobile device like iPad or iPod to open, view, and revise DWG files.

One of the most popular downloads among Autodesk software posted to Apple app store turns out to be SketchBook Mobile, an intuitive paint-draw software that lets you mimic the paper-based workflow. Made available on iPad, iPod, iPhone, and (most recently) Android, the $0.99 program has been successful “beyond our wildest dream,” said Autodesk Labs’ VP Brian Matthews.

Later, in the Technology Main Stage panel discussion, Kowalski offered some of his own ideas about how infinite computing, coupled with omnipresent broadband connectivity, might enable us to live and work.

“I want data to follow me; I want content to follow,” he said. “And I want the spaces around us to react to our presence.”

The switch “from scarcity and conservation to abundance [of computing power],” as Bass put it, is bound to give many engineers and designs a chance to try out computational experiments previously impossible to undertake. Here’s hoping we will learn to wield it responsibly.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE