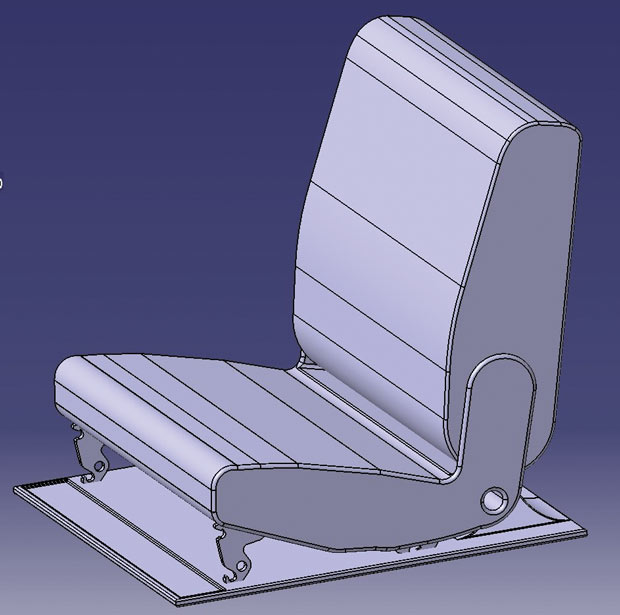

CAD overlay (grey rectangles at bottom) shows how the two bench-seat attachments fit to the legs of the Jeep seat to protect it from contact with the ground. Image courtesy of Patrick Bright.

Latest News

December 1, 2015

Patrick Bright was camping with some friends in the mountains of Northern Arizona when he came up with the idea for his class project. An engineering student at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Prescott, AZ, Bright was in his junior year and had recently signed up for course ME 428: Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DFMA). It was uncharted territory for Bright, but based on the syllabus he figured it would be a good way to learn more about manufacturing, a topic he’d long been interested in.

He wasn’t disappointed.

Before applying for admission to Embry-Riddle, Bright served in the Marine Corps. Through it all he had his sights set on a career in aerospace engineering, but thought he might not be talented enough for the grueling academic work required with this most demanding of degrees. Thankfully, he was proven wrong. “I’ve had some great mentors who showed me I could achieve whatever I put my mind to,” says Bright. “Because of them, I started looking for good aerospace universities worldwide after leaving the Corps., Embry-Riddle was right at the top.”

Back to School

One of Bright’s mentors is the instructor for ME 428, Dr. Alfredo Herrera, who says the DFMA course is designed to teach the basics of machining, molding, forming, stamping and other manufacturing processes commonly used in the aerospace industry, as well as best practices on product design such as part dimensions and tolerances, material properties and selection, cost determination, and so on.

CAD overlay (grey rectangles at bottom) shows how the two bench-seat attachments fit to the legs of the Jeep seat to protect it from contact with the ground. Image courtesy of Patrick Bright.

CAD overlay (grey rectangles at bottom) shows how the two bench-seat attachments fit to the legs of the Jeep seat to protect it from contact with the ground. Image courtesy of Patrick Bright.“The methodology I use when teaching the class is to take the students from an initial understanding of product design requirements using a Quality Function Deployment document, or QFD,” Herrera says. “Once they’ve done that, they’re ready to develop different concepts, and then perform a ‘down’ selection. Students look at the different opportunities within each concept, and then fine tune based on DFMA principles to develop the most robust design possible.”

Much of this iterative process utilizes a set of DFMA tools offered by Boothroyd Dewhurst Inc., an engineering software company based in Wakefield, RI. The company’s Design for Assembly Product Simplification (DFA) software walks engineers through a series of questions that help identify areas for improvement in a product or assembly. Minimum part count, assembly methods, dimensional information and component handling considerations — DFA gathers this information and analyzes it for potential redesign and part-consolidation reviews by the lead engineer and team.

The second leg of the part-analysis journey is DFM Concurrent Costing, which complements DFA by providing a “should cost” view of manufactured products. Key cost drivers are determined based on geometry, part tolerance, surface finish, and the optimal manufacturing processes and sequences offered by the software. The analysis allows designers to immediately understand the ramifications of their part design decisions. It is also an excellent negotiating tool that promotes transparency in the quoting process, and provides benchmarks against which to measure the efficiency of both external and internal suppliers.

Lessons Learned by the Campfire

Bright didn’t know any of this as he sat in front of his tent, roasting hotdogs. What he did know was this: the bench seat of his 2010 Jeep Wrangler — which he’d removed at the campsite so he had something to sit on — wanted to tip over. “It wasn’t very stable, and I was concerned about rocks and dirt getting into the connectors on the bottom of the seat,” Bright says. “I got to thinking about a platform of some kind, one that would make the Jeep seat more usable and easier to carry.”

And so the focus for Bright’s DFMA class project was born. He knew it would be a good opportunity to understand the lifecycle of a product from concept through manufacturing, and he might just get a nifty camping accessory as well. Following the DFMA process, Bright began to outline the design requirements for his concept, now dubbed the Outdoor Bench Seat Attachment, and determined that the ideal product would:

- Be of a size and weight suited to accompany the average customer’s camping supplies, given the cargo space of the intended vehicle.

- Require no more than two persons to deploy.

- Provide a reasonable amount of ground clearance to enable its use on moderately rocky, muddy, or snow covered terrain.

- Be offered at an initial price not to exceed $60.

Keeping It Simple

Bright went back to the drawing board. His second design concept was for a set of machined aluminum platforms with locking pins. This would bring the total part count to just four pieces and eliminate any assembly time. He soon learned an important lesson, however, one that is a core principle of DFMA: Keep it simple. “I’d intended to machine a pocket that would capture the front connector assembly, and a depression at the back of the platform to cradle the rear connector,” Bright says. “But it was a struggle just to model it all, and it didn’t take long to realize the machining would likewise be a challenge. Because the DFMA process identifies part complexity as a major cost driver, I abandoned that design shortly thereafter.”

Final renderings of the first-generation two bench-seat attachments Bright designed to support the feet of a Jeep back seat after its removal from the vehicle. Image courtesy of Patrick Bright.

Final renderings of the first-generation two bench-seat attachments Bright designed to support the feet of a Jeep back seat after its removal from the vehicle. Image courtesy of Patrick Bright.Aside from a hard-earned lesson in the simplification principle, Bright also learned an important part of DFMA methodology: that you don’t have to go through the entire design process before recognizing you’ve taken a wrong turn. He stepped back, took a critical look at what he’d done, and shifted gears to a thermoform molded-part design, one quite similar to his machined platforms but far simpler to manufacture. By selecting from various presets in the DFMA software, Bright was able to assess tooling and operating costs, anticipated cycle times based on material selection and type of molding machine, the cost impact of soft vs. hard tooling, and a host of other values, many of which can be edited to fit the actual conditions used during part manufacture.

Bright quickly found he had a winner design. The DFMA software estimated a 3-minute cycle time, compared to 12 minutes for the baseline. And with the greatly reduced part count and lower material cost, the molded product showed a savings of 89% over the original design. There remained room for additional refinements, of course, but the software helped in this respect as well, offering several suggestions to help Bright down a path of continuous improvement.

Hindsight is Always 20/20

There’s far more to DFMA than a software package, however. Dr. Herrera was there as a sounding board through the entire design process, presenting alternatives and encouraging Bright to share his findings with other students. “Dr. Herrera had helpful input on most of my ideas,” Bright says. “If I was stumped by something, he’d offer suggestions, or point me in a different direction. He was very instrumental in my understanding of DFMA.”

In fact, Bright took away a number of lessons that had nothing to do with Boothroyd Dewhurst’s product costing and simplification tools. Garnering input from colleagues and potential customers — an ad hoc market survey, if you will — earlier in the design process would have helped expedite product development, Bright says. “You have to fully embrace DFMA to realize the most benefit. You can’t just pick and choose which parts of the methodology you think work best. That means bringing in the design engineers, the marketing department, assembly line technicians — we all need to work together. When you use every aspect of DFMA, it comes together to form a powerful system.”

He also learned it’s important to faithfully use the complete functionality of the DFMA software, something he admits to skimping on in the initial baseline design. “I used the DFA product simplification tool to decide whether or not to go forward with a design,” says Bright. “It was very helpful in reducing the time spent on any given concept — with the baseline, for example, there were a lot of red flags, so it quickly became clear the design needed improvement. But the DFM concurrent costing tool is just as important. Each highlights different problem areas, and gives you the opportunity to compare them. I honestly feel both should be used at each point in the design process, to provide a complete view of the design and manufacturing equation.”

Next Steps and the Fruits of Collaboration

Bright has since sold his Jeep Wrangler. He says he misses it, and looks forward to the day he can replace it with another sport utility vehicle so he can go camping again. His Outdoor Bench Seat Attachment remains in the concept phase of its lifecycle, yet that will likely change as Bright’s graduation gets closer. He’s spoken with molding houses about the product’s manufacturability, is putting together a business plan, and will be building a prototype for display to potential customers. He’s also working on another project, this time with fellow student, Alan Marlowe.

“We’re working through the design process together,” says Bright. “With my DFMA knowledge, and his knowledge of 3D modeling, it’s a collaborative effort. I remember one instance where he was designing a complicated portion of the product and I told him, ‘You know, we don’t really need that to be tightly toleranced. Let’s cut back on the intricacy a little bit.’ That was one of the instances where collaboration played a big role, because he would have gone ahead and finished the design, thinking he was doing a good job. It would then come to me for DFMA analysis, and I’d have to send it back to him for rework.

The next iteration of Bright’s Outdoor Bench Seat Attachment is a light, strong, weatherproof rubber mat with rear-seat supports built directly into it. The concept defined through the use of DFMA remains the same, but Bright and Marlowe used the software to further reduce the part count from two parts to one. Image courtesy of Patrick Bright.

The next iteration of Bright’s Outdoor Bench Seat Attachment is a light, strong, weatherproof rubber mat with rear-seat supports built directly into it. The concept defined through the use of DFMA remains the same, but Bright and Marlowe used the software to further reduce the part count from two parts to one. Image courtesy of Patrick Bright.“This is why I’m such a fan of the DFMA methodology and the software Boothroyd Dewhurst offers to support it. They’re both important tools in today’s manufacturing world.”

In addition to this new project, Bright and Marlowe are working on the next iteration of the Outdoor Bench Seat Attachment. “I knew my product design wasn’t complete,” says Bright. “Knowing his and my engineering intuition complement each other, I requested his input. He immediately asked if the concept could be adapted to nullify the clearance requirement by offering a different solution. Once we get funding, I strongly believe we will take this new model to manufacture.”

Bright says the concept defined through use of DFMA remains the same, he and Marlowe just found another way to implement it while further reducing the part count from two down to one. “Again, the collaborative process is key,” says Bright. “It is amusing that Alan’s learned enough from me to start making DFMA friendly adjustments to his submitted work before allowing me to complete giving my input.”

More Info

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News