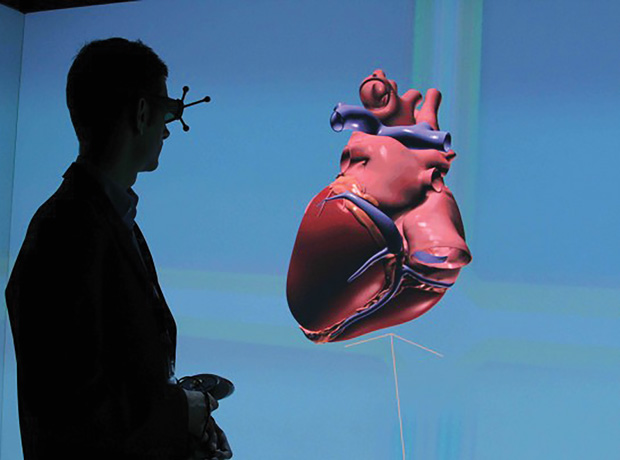

Interacting with a virtual heart in a virtual cave, made possible in Dassault Systèmes’ Living Heart Project. Image courtesy of Dassault Systèmes.

Latest News

August 1, 2016

Interacting with a virtual heart in a virtual cave, made possible in Dassault Systèmes’ Living Heart Project. Image courtesy of Dassault Systèmes.

Interacting with a virtual heart in a virtual cave, made possible in Dassault Systèmes’ Living Heart Project. Image courtesy of Dassault Systèmes.In the beginning, AutoCAD was the same. Whether you used it for architecture, industrial design, mechanical design or electrical design, you used the same 2D drafting and drawing features. Working with a product built for the widest possible horizontal, you learned to come up with creative solutions (or clumsy workarounds) to accomplish the tasks unique to your discipline, domain or niche.

It’s quite different today. The drawing environment for AutoCAD Architecture—the version that Autodesk markets to the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry—is tailored to help you parametrically draw adjustable windows, doors and walls. By contrast, AutoCAD MEP—for the mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems designers—comes with blocks and orthographic symbols specific to the intended field. And AutoCAD Electrical has a layout environment designed for creating schematics with electrical connections, voltages and circuits. A timeline chronicling the first releases of these special AutoCAD versions would offer good insight into the moments Autodesk decided to expand into new verticals.

Design software makers like Autodesk constantly weigh the pros and cons of emerging markets to explore. Sometimes they acquire an established vendor in the target sector to use as their launch pad. Other times they spinoff a new edition or flavor of an existing product. When the needs of the new market are too eccentric (like the physics required to simulate fabrics in fashion and apparel, or the surface-modeling features needed to design prosthetics), vendors face a dilemma: Make radical changes to the core product to appeal to the new users, or leave the field open for someone else to tackle.Forging a Path into New Verticals

Earlier this year, Autodesk decided its product offerings had grown too complex. The company offered a number of suites, each targeting a specific vertical: Building Design Suite for AEC; Product Design Suite for mechanical design and manufacturing; Entertainment Creation Suite for content creators, game developers and filmmakers; Factory Design Suite for factory designers; Plant Design Suite for plant managers; and so on. But many suites were also subdivided into Standard, Premium and Ultimate editions containing varying degrees of functionalities.

“[The suites] gave customers a lot of choices, but also created a lot of confusion,” says Carl White, Autodesk’s senior director of Business Models. The company’s strategy was to reduce its bundles to three Industry Collections, reflecting the three core verticals it historically serves:

• Architecture, Engineering and Construction Collection

• Product Design Collection

• Media and Entertainment Collection

About the new collections, White says, “We’re trying to put together the greatest number of relevant products at the right price point for most customers.” The new Industry Collections are not subdivided into three tiers like the predecessor suites.

“We do go after verticals, but we tend to pick the broadest vertical we can go into,” White adds. The company’s acquisitions of HSMWorks in 2012 and Delcam in 2014 laid the foundation for its expansion into the computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) market, considered to be closely tied to the company’s core businesses in CAD and computer-aided engineering (CAE).

Though the company shows no interest in straying too far from its core competency, it has begun to encourage others to develop products for the underserved industries using Autodesk Forge, a set of cloud services that connects design, engineering, visualization, collaboration, production and operation workflows. Forge is a set of APIs (application programming interfaces) that allow developers to tap into the modeling, drawing, visualization, simulation, and data-management technologies from Autodesk. It’s the same platform used by Autodesk to build its own products. (Editor’s note: See page 7 for more information.)

The Heart of the Strategy

Historically a CAD and product lifecycle management (PLM) company, Dassault Systèmes took bold steps to expand its life sciences footprint into the biomedical field with the acquisition of Accelrys in 2014. The San Diego-based Accelrys specializes in biological, chemical and material modeling, simulation and production domains. Among its 2,000 customers were Sanofi, Pfizer, Unilever NV and L’Oreal SA. In May of 2014, Dassault Systèmes launched its new brand BIOVIA, described as a combination of its “own activities in BioIntelligence, its collaborative 3DEXPERIENCE technologies, and the leading life sciences and material sciences applications from the recent acquisition of Accelrys.”

This is expanding into new territories for Dassault Systèmes, mostly known for its solutions and experience with automotive and aerospace manufacturers. “We offer a full range of solutions to support innovation from pharmaceuticals to medical device to healthcare companies, leveraging the power and collaboration benefits of the 3DEXPERIENCE platform and the integration with BIOVIA applications,” says Jean Colombel, VP of Life Sciences at Dassault Systèmes.

One of Dassault Systèmes’ notable offerings in this field is The Living Heart, a 3D digital realistic model of a human heart. “We have partnered with over 100 medical experts in the field of cardiology, working in collaboration with clinicians, designers and regulators,” Colombel says. “The first model we built is based on a healthy human adult and we can create other models from this one. You can use The Living Heart straight out of the box. If you’re a medical professional or a medical device researcher, you could use it, for example, to develop a new kind of cardiac valve and test it in silico. We provide a predefined set of characteristics related to the human body. You can then also customize [the digital heart] further with results from your own research.”

For blood flow and muscle movement simulation, The Living Heart uses SIMULIA, the same Dassault Systèmes technology deployed by car and plane manufacturers, but with a twist. “On top of SIMULIA, we put a layer specific to the design of heart valves and medical devices. And we make sure we use the right medical properties,” says Colombel.

In November 2014, Dassault Systèmes signed a five-year collaborative research agreement with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The joint announcement explained the company and FDA “will initially target the development of testing paradigms for the insertion, placement, and performance of pacemaker leads and other cardiovascular devices used to treat heart disease.”

Targeting a specialized industry like medical device makers requires a good understanding of their workflow, and tailor-made features to meet their regulatory needs. “Medical device manufacturers have to organize knowledge around what’s called a design history file (DHF) when they ask for market registration to comply with regulatory demands,” says Colombel. “The same type of information exists in the software for automotive or aerospace, but it has to be organized, named, captured, collected and presented in a specific way for Life Sciences DHF filing.”

DHF change management is part of Dassault Systèmes’ project management offerings under the 3DEXPERIENCE platform. It’s described as “advanced project management capabilities for medical device companies to … coordinate project activities and deliverables to ensure completion of design control deliverables and automatically populates the resulting DHF.”

Sailing into Energy and Shipbuilding

Siemens PLM Software, a division of Siemens, uses what it calls Industry Catalysts as launch pads to move into specific verticals. “Eighty to 90% of the product is exactly the same; but that remaining 10-20% has to tailor to the specific industry. We have expertise in many core industries; in others we leverage our partners,” says Tony Hemmelgarn, executive VP of Global Sales, Marketing and Service Delivery for Siemens PLM Software.

When the company wanted to offer a bid response solution to the energy sector, it chose Accenture as its partner. “When an energy company wants to respond to a bid, there are lots of documents they need to pull together. The terms they use and the way they do that is different from other industries. Our partner in that area is Accenture,” Hemmelgarn explains.

In May 2015, Siemens PLM Software announced “a new PLM software and services solution aimed at enhancing efficiency for the global Energy & Utilities industry.” The solution is part of Siemens’ Industry Catalyst Series offerings. The company writes: “it leverages Siemens’ Teamcenter portfolio to digitalize key capital project management processes, such as bid response management, and is specifically tailored to critical Energy & Utilities industry business processes.” Siemens praises project partner Accenture for its “deep industry knowledge and implementation experience.”

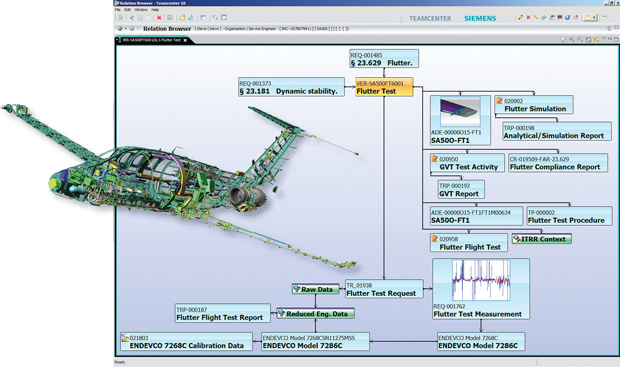

Teamcenter’s relationship browser provides a snapshot of requirements verification, offering traceability from requirement to compliance. Image courtesy of Siemens PLM Software.

Teamcenter’s relationship browser provides a snapshot of requirements verification, offering traceability from requirement to compliance. Image courtesy of Siemens PLM Software.Another Industry Catalyst from Siemens PLM Software targets the shipbuilding industry. “Most Industry Catalysts are an integration of our products. But for shipbuilding, we added capabilities to track and consume weight information along the lifecycle of the ship configuration. This data is then submitted to the weight computation specialists for shipyard-specific weight calculations,” says Hemmelgarn.

The company writes: “The shipbuilding catalyst delivers industry best practice models that function as references for PLM across the entire product lifecycle. Deployment accelerators include recommended product selections, network design decisions, configuration procedures, deployment best practices and user training. Open and configurable shipbuilding software allows you to control the appearance and behavior of a Siemens PLM implementation. These include data model extensions, data structures, and validation checks.”

The more eccentric the workflow, the more effort is required to tailor the code and user interface (UI). “It’s easy to put a thin layer or a wraparound [on a product]. But that won’t get you want you want,” recalls Hemmelgarn. “When we did a process for airplane certification, we had all the required technology components. But we’d never linked a process together from a manufacturer’s point of view. It required leveraging people in the industry to help us get it right. In that case, we had to have full traceability, facilitated through Teamcenter requirements management, with linkages to CAD authoring tools.”

Open Opportunities for Partners

Some verticals will inevitably be too vertical, too narrow a niche for industry leading vendors to pursue. “If we have to make radical changes to the way our product work, and the market is so small, then it doesn’t make sense to us,” Hemmelgarn says. So pockets of opportunities are left to third-party developers and software partners with sufficient domain knowledge.

For example, OPTIS, a Deluxe partner of Siemens PLM Software, offers light simulation and prototyping solutions that “help businesses and people to optimize perceived quality and visual signature of their future product.” The software’s integration with NX, Siemens PLM Software points out, offers “advanced light and optical simulation directly integrated in their overall product design process.” Most people don’t associate Dassault Systèmes’ CATIA design program with architecture, but it is the foundation for Gehry Technologies’ Digital Projects, an architectural modeling program.

Sandip Jadhav, CEO of simulationHub, develops and markets a series of simulation apps based on Autodesk’s Forge APIs. The selection is currently available as beta versions. It features ventilation analysis for conceptual houses, flow simulation for butterfly valves, and turbulent flow analysis for cyclone separators. The preconfigured templates allow people with limited expertise in simulation to conduct specific types of analysis without learning or purchasing a general-purpose computational fluid dynamic (CFD) package.

As a general-purpose design product gains widespread adoption in a certain industry, the industry’s special needs and eccentricities begin to reshape the product itself. Thus, many CAD, CAM and CAE software vendors find themselves at a crossroad as they begin exploring industries beyond their principal domains—automotive and aerospace manufacturing. The opportunities in emerging fields like IoT, biomedical, life sciences and medical devices beckon. But to pursue them, developers would need to put in significant code refinement and UI changes.

“We think it absolutely requires tailoring the software to specific industries. We really got down to the nomenclature and verbiage,” remarks Siemens PLM Software’s Hemmelgarn.

More Info

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kenneth Wong is Digital Engineering’s resident blogger and senior editor. Email him at [email protected] or share your thoughts on this article at digitaleng.news/facebook.

Follow DE